Flyweight

Also known as: Cache

Intent

Flyweight is a structural design pattern that lets you fit more objects into the available amount of RAM by sharing common parts of state between multiple objects instead of keeping all of the data in each object.

Problem

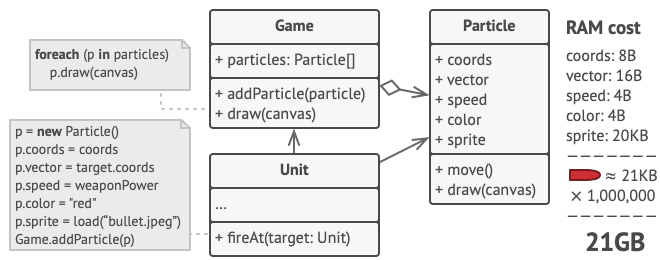

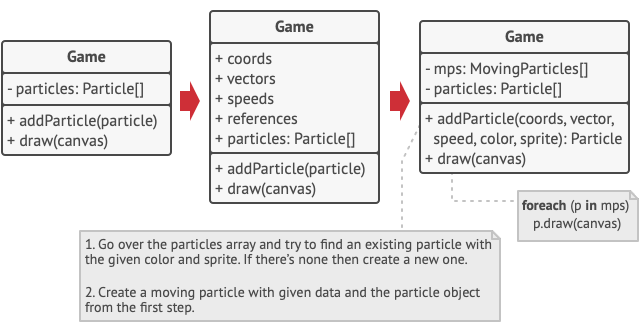

To have some fun after long working hours, you decided to create a simple video game: players would be moving around a map and shooting each other. You chose to implement a realistic particle system and make it a distinctive feature of the game. Vast quantities of bullets, missiles, and shrapnel from explosions should fly all over the map and deliver a thrilling experience to the player.

Upon its completion, you pushed the last commit, built the game and sent it to your friend for a test drive. Although the game was running flawlessly on your machine, your friend wasn’t able to play for long. On his computer, the game kept crashing after a few minutes of gameplay. After spending several hours digging through debug logs, you discovered that the game crashed because of an insufficient amount of RAM. It turned out that your friend’s rig was much less powerful than your own computer, and that’s why the problem emerged so quickly on his machine.

The actual problem was related to your particle system. Each particle, such as a bullet, a missile or a piece of shrapnel was represented by a separate object containing plenty of data. At some point, when the carnage on a player’s screen reached its climax, newly created particles no longer fit into the remaining RAM, so the program crashed.

On closer inspection of the Particle class, you may notice that the color and sprite fields consume a lot more memory than other fields. What’s worse is that these two fields store almost identical data across all particles. For example, all bullets have the same color and sprite.

Other parts of a particle’s state, such as coordinates, movement vector and speed, are unique to each particle. After all, the values of these fields change over time. This data represents the always changing context in which the particle exists, while the color and sprite remain constant for each particle.

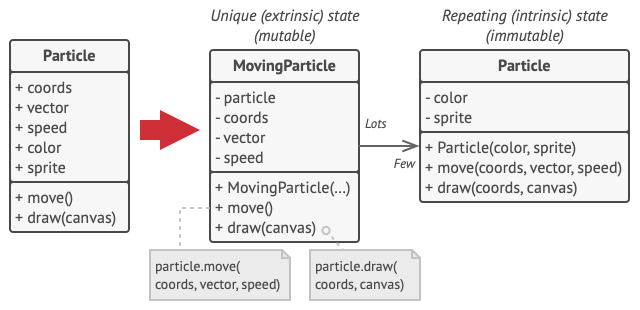

This constant data of an object is usually called the intrinsic state. It lives within the object; other objects can only read it, not change it. The rest of the object’s state, often altered “from the outside” by other objects, is called the extrinsic state.

The Flyweight pattern suggests that you stop storing the extrinsic state inside the object. Instead, you should pass this state to specific methods which rely on it. Only the intrinsic state stays within the object, letting you reuse it in different contexts. As a result, you’d need fewer of these objects since they only differ in the intrinsic state, which has much fewer variations than the extrinsic.

Extrinsic state storage

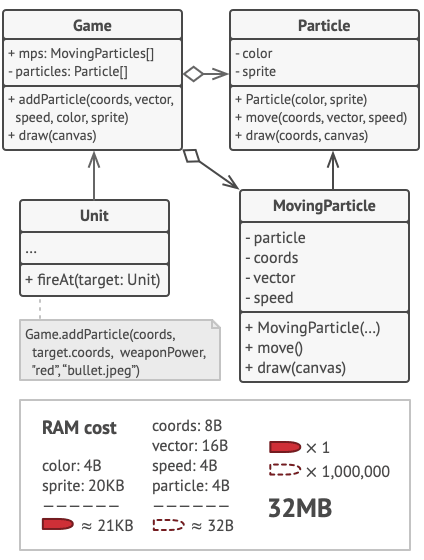

Where does the extrinsic state move to? Some class should still store it, right? In most cases, it gets moved to the container object, which aggregates objects before we apply the pattern.

In our case, that’s the main Game object that stores all particles in

the particles field. To move the extrinsic state into this class, you

need to create several array fields for storing coordinates, vectors,

and speed of each individual particle. But that’s not all. You need

another array for storing references to a specific flyweight that

represents a particle. These arrays must be in sync so that you can

access all data of a particle using the same index.

A more elegant solution is to create a separate context class that would store the extrinsic state along with reference to the flyweight object. This approach would require having just a single array in the container class.

Wait a second! Won’t we need to have as many of these contextual objects as we had at the very beginning? Technically, yes. But the thing is, these objects are much smaller than before. The most memory-consuming fields have been moved to just a few flyweight objects. Now, a thousand small contextual objects can reuse a single heavy flyweight object instead of storing a thousand copies of its data.

Flyweight and immutability

Since the same flyweight object can be used in different contexts, you have to make sure that its state can’t be modified. A flyweight should initialize its state just once, via constructor parameters. It shouldn’t expose any setters or public fields to other objects.

Flyweight factory

For more convenient access to various flyweights, you can create a factory method that manages a pool of existing flyweight objects. The method accepts the intrinsic state of the desired flyweight from a client, looks for an existing flyweight object matching this state, and returns it if it was found. If not, it creates a new flyweight and adds it to the pool.

There are several options where this method could be placed. The most obvious place is a flyweight container. Alternatively, you could create a new factory class. Or you could make the factory method static and put it inside an actual flyweight class.

Structure

-

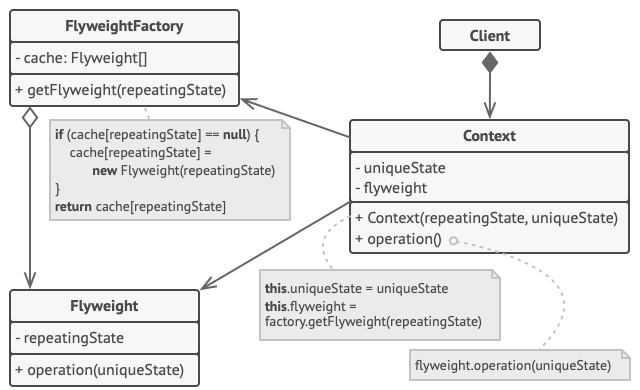

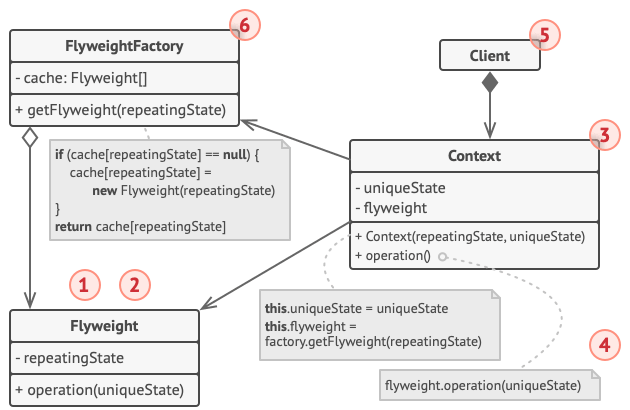

The Flyweight class contains the portion of the original object’s state that can be shared between multiple objects. The same flyweight object can be used in many different contexts. The state stored inside a flyweight is called intrinsic. The state passed to the flyweight’s methods is called extrinsic.

-

The Context class contains the extrinsic state, unique across all original objects. When a context is paired with one of the flyweight objects, it represents the full state of the original object.

-

Usually, the behavior of the original object remains in the flyweight class. In this case, whoever calls a flyweight’s method must also pass appropriate bits of the extrinsic state into the method’s parameters. On the other hand, the behavior can be moved to the context class, which would use the linked flyweight merely as a data object.

-

The Client calculates or stores the extrinsic state of flyweights. From the client’s perspective, a flyweight is a template object which can be configured at runtime by passing some contextual data into parameters of its methods.

-

The Flyweight Factory manages a pool of existing flyweights. With the factory, clients don’t create flyweights directly. Instead, they call the factory, passing it bits of the intrinsic state of the desired flyweight. The factory looks over previously created flyweights and either returns an existing one that matches search criteria or creates a new one if nothing is found.

Pseudocode

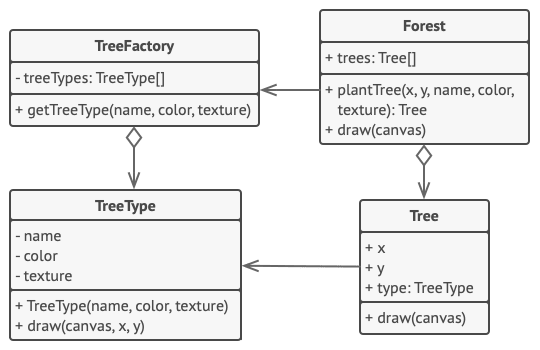

In this example, the Flyweight pattern helps to reduce memory usage when rendering millions of tree objects on a canvas.

Now instead of storing the same data in multiple objects, it’s kept in just a few flyweight objects and linked to appropriate Tree objects which act as contexts. The client code creates new tree objects using the flyweight factory, which encapsulates the complexity of searching for the right object and reusing it if needed.

// The flyweight class contains a portion of the state of a

// tree. These fields store values that are unique for each

// particular tree. For instance, you won't find here the tree

// coordinates. But the texture and colors shared between many

// trees are here. Since this data is usually BIG, you'd waste a

// lot of memory by keeping it in each tree object. Instead, we

// can extract texture, color and other repeating data into a

// separate object which lots of individual tree objects can

// reference.

class TreeType is

field name

field color

field texture

constructor TreeType(name, color, texture) { ... }

method draw(canvas, x, y) is

// 1. Create a bitmap of a given type, color & texture.

// 2. Draw the bitmap on the canvas at X and Y coords.

// Flyweight factory decides whether to re-use existing

// flyweight or to create a new object.

class TreeFactory is

static field treeTypes: collection of tree types

static method getTreeType(name, color, texture) is

type = treeTypes.find(name, color, texture)

if (type == null)

type = new TreeType(name, color, texture)

treeTypes.add(type)

return type

// The contextual object contains the extrinsic part of the tree

// state. An application can create billions of these since they

// are pretty small: just two integer coordinates and one

// reference field.

class Tree is

field x,y

field type: TreeType

constructor Tree(x, y, type) { ... }

method draw(canvas) is

type.draw(canvas, this.x, this.y)

// The Tree and the Forest classes are the flyweight's clients.

// You can merge them if you don't plan to develop the Tree

// class any further.

class Forest is

field trees: collection of Trees

method plantTree(x, y, name, color, texture) is

type = TreeFactory.getTreeType(name, color, texture)

tree = new Tree(x, y, type)

trees.add(tree)

method draw(canvas) is

foreach (tree in trees) do

tree.draw(canvas)Applicability

Use the Flyweight pattern only when your program must support a huge number of objects which barely fit into available RAM.

The benefit of applying the pattern depends heavily on how and where it’s used. It’s most useful when:

- an application needs to spawn a huge number of similar objects

- this drains all available RAM on a target device

- the objects contain duplicate states which can be extracted and shared between multiple objects

How to Implement

-

Divide fields of a class that will become a flyweight into two parts:

- the intrinsic state: the fields that contain unchanging data duplicated across many objects

- the extrinsic state: the fields that contain contextual data unique to each object

-

Leave the fields that represent the intrinsic state in the class, but make sure they’re immutable. They should take their initial values only inside the constructor.

-

Go over methods that use fields of the extrinsic state. For each field used in the method, introduce a new parameter and use it instead of the field.

-

Optionally, create a factory class to manage the pool of flyweights. It should check for an existing flyweight before creating a new one. Once the factory is in place, clients must only request flyweights through it. They should describe the desired flyweight by passing its intrinsic state to the factory.

-

The client must store or calculate values of the extrinsic state (context) to be able to call methods of flyweight objects. For the sake of convenience, the extrinsic state along with the flyweight-referencing field may be moved to a separate context class.

Pros and Cons

Pros

- You can save lots of RAM, assuming your program has tons of similar objects.

Cons

- You might be trading RAM over CPU cycles when some of the context data needs to be recalculated each time somebody calls a flyweight method.

- The code becomes much more complicated. New team members will always be wondering why the state of an entity was separated in such a way.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

You can implement shared leaf nodes of the Composite tree as Flyweight to save some RAM.

-

Flyweight shows how to make lots of little objects, whereas Facade shows how to make a single object that represents an entire subsystem.

-

Flyweight would resemble Singleton if you somehow managed to reduce all shared states of the objects to just one flyweight object. But there are two fundamental differences between these patterns:

- There should be only one Singleton instance, whereas a Flyweight class can have multiple instances with different intrinsic states.

- The Singleton object can be mutable. Flyweight objects are immutable.